Introduction

This work was inspired by the observation that most research on eye gaze and speech has focused on behavior in unnatural situations (e.g., faces speaking single words). Furthermore, typical measures of eye gaze behavior that had been applied in previous research (e.g., fixation duration, saccade rate) only described a behavior averaged over listeners and over time. To be able to use eye gaze for audiological applications, we need methods that access a more nuanced and detailed description.

This work has been partially supported by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, VR 2017-460 06092 418 Mekanismer och behandling vid åldersrelaterad hörselnedsättning).

Aims

This project aims at generating knowledge that would guide how eye gaze can be used in audiological applications. Potential applications included both the possibility for eye gaze as a control signal in hearing aids but also as a measure of listeners’ experience in real-world settings.

The purpose of this project is (1) to generate a basic understanding of how listeners use their gaze in realistic conversations, and (2) to gain experience generating and analyzing this type of data.

Methodology

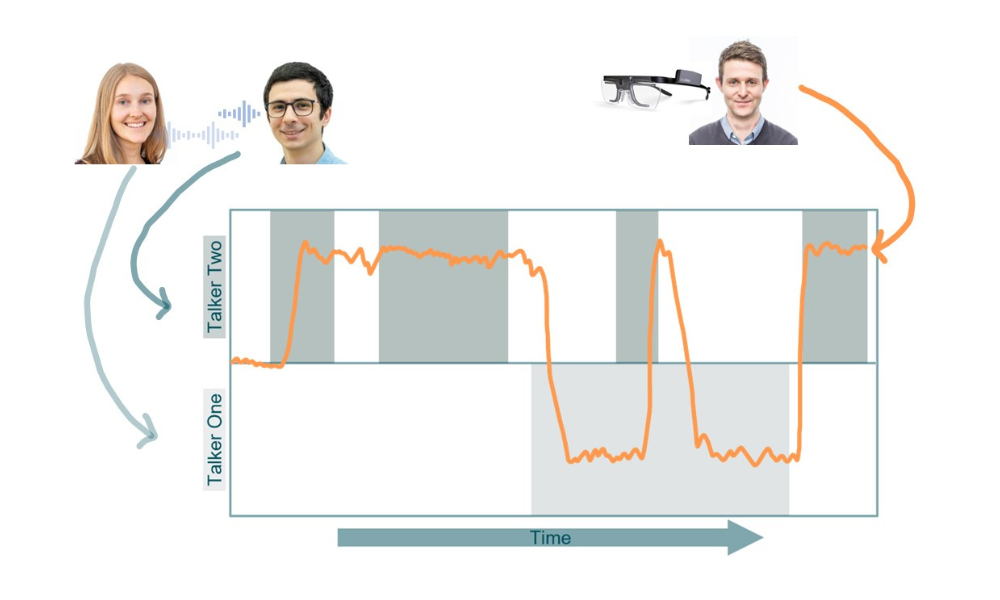

We collected data from hearing-impaired participants while they followed a pre-recorded audio-visual conversation with two talkers.

We studied eye gaze behavior under different conversational turn taking categories using multi-level logistic regression.

Results

We found that when listeners followed a pre-recorded conversation between two talkers, they showed similar eye gaze behaviours at different parts of the conversation. Eye gaze behaviour changed a lot though over different parts of the conversation. This means that there is an advantage for future research on gaze in realistic conversation to use pre-recorded stimuli and Multi level modelling, because it allows control for the idiosyncratic nature of realistic conversation.

We also calculated that, between 65 and 80% of the time, listeners looked at the talker who was taking their speaking turn. There was no systematic change in this percentage when there were pauses, interruptions, or changes between the talkers.

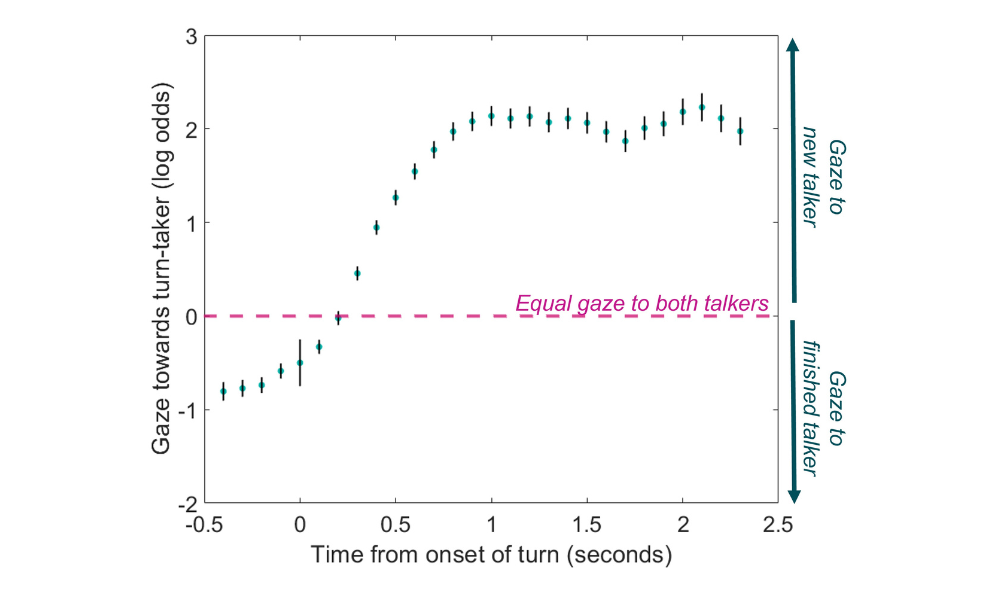

Finally, we observed that when the talkers took turns in the conversation, the listeners tended to look at the new talker by 200 ms after the onset of that talkers’ speech, and the highest chance of looking at the new talker occurred 1.4 seconds after this onset.

This figure illustrates the probably (log odds) of the listener’s gaze to the new talker in a conversational turn (floor transfer) over time. We can observe that listeners start looking at a new talker 200 ms after they start talking